What breeds lurk in the Ridgeback’s genes? Now, scientists can tell us.

If you’re a Ridgeback history junkie, prepare to become very, very excited.

Some breeds have the luxury of being founded by compulsive individuals with a knack for documentation. The early Boer architects of the Rhodesian Ridgeback, however, were more interested in shooting their supper and avoiding the rake of a leopard’s claws than noodling with pedigrees or preserving parentage. As a result, we have had a very tentative understanding of what breeds went into making the Rhodesian Ridgeback.

Until now.

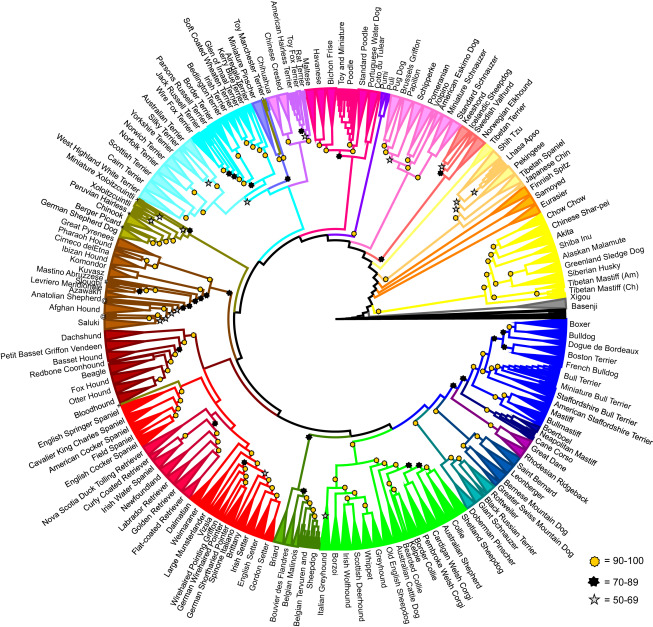

Earlier this week, Cell Reports magazine published a paper called “Genomic Analyses Reveal the Influence of Geographic Origin, Migration, and Hybridization on Modern Dog Breed Development.” To create what is the most diverse data set of dog breeds to date, the researchers studied 161 modern breeds, comparing 170,000 different points on their genomes. They identified 23 clades, or breed clusters, containing breeds that are significantly related.

A graphic showing the 23 clades identified by the researchers. Proximity to another clade is not relevant; what matters are the dogs that share the same color, which reflects their shared genetic heritage. Look for the Ridgeback in the hot-pink clade at about positioned at about the four-o’clock mark.

“There are different reasons logically that a breed could be assigned to a clade,” explains one of the paper’s authors, Dr. Dayna Dreger of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. “Its breeds might be derived from a common source, or it could reflect that there was introgression of one breed into another.”

The scientists assigned the Rhodesian Ridgeback to a clade that has just one other breed:

The Great Dane.

Recruit of Foxbar, a female Great Dane from the 1930s.

If you know your breed history, that canine connection doesn’t come totally out of left field: In her seminal book Rhodesian Ridgeback Pioneers, author Linda Costa shares correspondence from De Beers Ranch officials in Rhodesia in the early 1920s that outlines the diamond mine’s plans to breed Lion Dog sires to recently procured Great Dane bitches. The planned progeny were to be used to hunt vermin on the grounds of the diamond mines, including wild dogs. “I really want rough, big dogs,” one official wrote. ” … the pure Lion Dog appear [sic] too small for the use I need them for in Rhodesia.”

Photographs of Great Danes from the early-20th Century-show dogs that were more moderate in size and type than today’s much more stylized Danes — not too far removed from a modern Ridgeback. And some might argue that Great Dane type is one of the strongest drags on the breed today, manifesting in over-standard size, relative narrowness for that ample height, a squarer silhouette, excessive haw and flews, black masks that extend over the eyes and an overall “extreme” outline.

In addition to grouping breeds into these related clades, the researchers delved into breed make-up. “The paper looked across the admixture of how are breeds created — what was mixed with what to create what,” says Dr. Elaine Ostrander, another of the paper’s authors, who is world famous for her work in purebred-dog genetics.

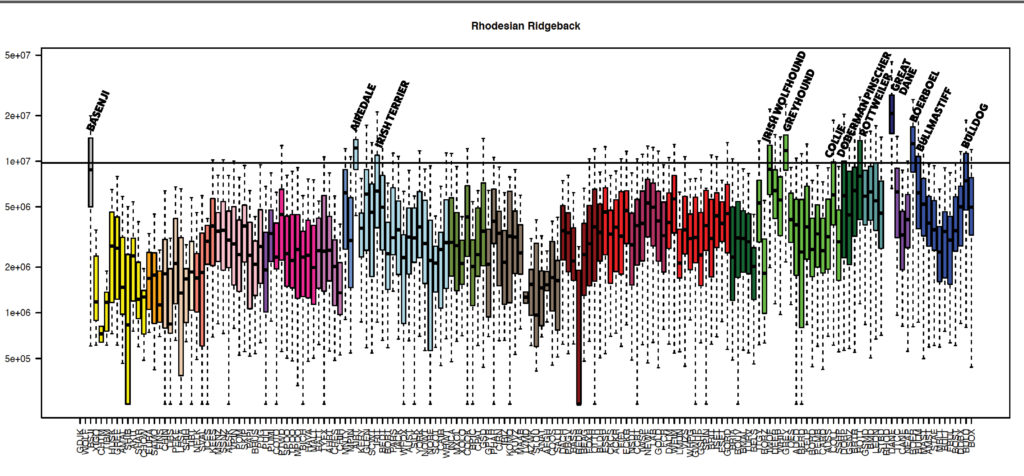

At left are the paper’s findings of the significant genetic influences in the Rhodesian Ridgeback.

At left are the paper’s findings of the significant genetic influences in the Rhodesian Ridgeback.

Let’s take a look at some of the historical and geographic evidence we have of these breeds intersecting with the Ridgeback.

I’ve always found it interesting that there is very little cultural exchange between Rhodesian Ridgeback and Boerbel fanciers. In fact, many of the former are unaware that the Molosser-derived Boerboel developed in tandem with the Ridgeback in the same region of Africa. This lack of awareness could stem from the fact that the breeds had different emphases: Both are hunters and guardians, but the Ridgeback specializes in the former and the Boerboel in the latter. Perhaps the Ridgeback’s development to the north, in Rhodesia, further cementing the division between the two breeds, in the dog fancy at least.

At first glance, having the Basenji place so high on the list of Ridgeback-influencing breeds might seem odd, but this wrinkle-browed dog is a native African, so genetically unique that is has its own singular clade in the study. Sheer geography makes it logical that this purely African breed would have found its way into the Ridgeback gene pool, which is otherwise composed of Continental breeds brought to Africa by European colonizers. Dr. Ostrander notes wryly that the impact of one of the Ridgeback’s most important ancestors, the Khoikhoi dog, can’t be assessed because there are no surviving dogs to provide DNA, though a sampling of ridged Africanis dogs might be the next best thing. And those dogs might prove more closely connected to the Basenji themselves.

The rest of the breeds on the researchers’ list of Ridgeback “introgressors” are European. And they dovetail with surprising precision with the list of founding breeds proposed by the late Canadian breeder-judge David Helgesen in his self-published Definitive Rhodesian Ridgeback.

For the 1984 book, Helgesen analyzed period newspapers to determine what breeds were most common in turn-of-the-last-century Rhodesia, when the breed was formally developed by big-game hunter Cornelius van Rooyen. That, paired with anecdotal accounts of van Rooyen’s pack, led to his oft-repeated list of eight foundation breeds: Greyhound (for speed), Bulldog (for substance and biting power), Irish Terrier and Airedale (for tenacity, and, in the case of the Irish, coat color), Collie (for slashing ability), Pointer (for air scenting ability), Deerhound (for size as well as all the Greyhound’s advantages) and of course the Khoikhoi dog, which contributed the ridge, as well as unknown levels of native knowledge, disease resistance and local adaptability. Other than the Khoikhoi dog and the Irish Wolfhound (which is mostly made up of Deerhound blood, with still more Dane thrown in), only the Pointer is missing from the paper’s list of influential breeds in the Ridgeback — the only real stumper I find in these results.

Genome haplotype sharing for the Rhodesian Ridgeback, from “Genomic Analyses Reveal the Influence of Geographic Origin, Migration, and Hybridization on Modern Dog Breed Development.” Labels added by RidgebackCentral.com.

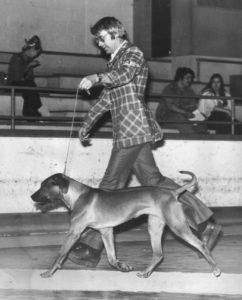

David Helgesen in the ring, 1970s.

Helgesen’s candidates aside, other breeds that come up in the modern DNA findings are logical fits, too. South African diamond mines also used Bullmastiffs for guard and patrol duty, and the Boerboel has a good infusion of Bullmastiff blood itself. Some lines of early Ridgebacks — in particular, Graham Stacey’s Dewsbury and Khami dogs, and those of Phyllis Archdale — had wiry coats accompanied by good size, which strongly evoke the Irish Wolfhound (and so, by extension, the Great Dane), and period articles also mention Wolfhounds being used for lion hunting in Africa. And the occasional black-and-tan has led many Ridgeback fanciers to assume that a two-tone breed — like a Doberman or Rottweiler — jumped the fence somewhere along the line.

In the end, what does all this provide us, other than cocktail-party fodder? For breeders, knowing the Ridgeback’s actual foundation breeds — as well as those that parachuted in later as it developed — helps us chart where our Ridgebacks are heading. Though those who wrote the first Ridgeback standard in 1922 were aiming for a souped-up version of the Dalmatian — that spotted breed’s standard was used to draft the Ridgeback’s, in some places word for word — none of the high-influence breeds in this new genomic study share that basic endurance-trotting silhouette. (Which makes the Pointer’s absence felt even more strongly.)

Ridgeback breeders need to be aware of the genetic influences of other breeds, such as the Great Dane, that can slowly chip away at their breeding programs.

Is it any wonder, then, that Ridgeback type can seem so infuriatingly elusive for those who try to pin it down, either in their whelping boxes, or in the show ring? By knowing what influences lie in the genes of our dogs, we can be more aware when they begin to push breed type in the wrong direction, like a sudden current angling a swimmer away from shore. After all, past is always prologue, and knowing where we’ve been helps us immeasurably in determining where to go next.

Calling all Ridgebacks: Drs. Ostrander and Dreger are looking for Ridgebacks from a variety of lines and countries to continue their genetic work. If you are willing to contribute a blood sample for this research, please contact me at denise@ridgebackcentral.com, and I will put you in touch.

Hope for Devastating Form of Epilepsy in Young Ridgebacks

I know last week I promised you another update on the 2016 Rhodesian Ridgeback World Congress – and pinky-promise, that’s coming – but today I want to share a group page that’s really blowing up on Facebook – and for all the right reasons.

Seemingly countless times a day, little pings from my phone and laptop tell me new members are being added to the fledgling Myoclonic epilepsy in rhodesian ridgebacks Facebook page. Last I checked, it was at almost 850 members.

Rhodesian Ridgebacks, like many dog breeds, can develop epilepsy: In the United States, the average age of onset for the breed is relatively late, usually around five years or six of age. But the form of epilepsy this Facebook page is devoted to appears much earlier, as young as six weeks, and as late as 18 months. Compared to “classic” epilepsy, this juvenile form is characterized by frequent muscle jerks or twitches, usually when the dog is sleeping or resting.

Videos of Ridgebacks having these shock-like seizures are quite heartbreaking: The poor dog is jarred and disoriented by the sudden episode, to say nothing of the traumatized owner.

“JME seems to run in many different lines,” explains Nina Lindqvist, founder of the Facebook group and chair of the Ridgeback club of Finland. “Therefore it is assumed that the mutation has already been in the breed for a very, very long time.”

Unfortunately, the long-term prognosis for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, or JME, in Rhodesian Ridgebacks is not very promising. Dogs can be treated with a variety of anti-convulsive drugs: Levetiracetam (sold under the brand name Keppra in the U.S.), which was developed to treat myoclonic seizures in children, seems to work best, but its efficacy in dogs often cannot be maintained in the long term.

The good news is that European researchers have been busy studying the disorder: In 2015, Andrea Fischer at Munich University in Germany formally identified JME through clinical examinations, and Hannes Lohi’s Koirangeenit group at the University of Helsinki in Finland has isolated the recessive gene responsible for the disease.

Of the 538 samples analyzed by the Finnish researchers, 15 percent were carriers and 4 percent were affected. (And Nina notes that all dogs carrying two copies of the JME gene tested thus far are symptomatic – it appears dogs cannot dodge this genetic bullet.) Though the sampling was very likely skewed in favor of dogs likely to be carriers, the statistics are nonetheless sobering.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that this is a problem more prevalent in Europe and the United Kingdom. There were reportedly no American dogs sampled for the study.

Now that the causal mutation for JME has been identified, breeders are clamoring for a test, which is in the offing, but not until 2017, after the researchers’ studies have been peer reviewed and published.

Later this week, results of dogs tested for the research will be made available on the Ridgeback Club of Finland’s website at www.ridgeback.fi, contingent on the permission of their owners, of course. (There will be a link on the Facebook page, too.) Armed with that information, breeders can avoid breeding dogs with unknown genotypes to confirmed carriers to prevent any new affected dogs from being born.

Once the commercial test is available, Nina stresses that carriers may then be safely bred to confirmed clear dogs to prevent the disease from expressing while maintaining all-important genetic diversity. Remember: Carriers do not have the disease, and can only produce it if bred to another carrier.

Breeders who think they may have inadvertently bred two carriers can contact Nina at nina@lumottu.net. You can also contact her if you have a dog who was tested for JME and wish to have the results made public.

Everyone else, patience and crossed fingers until the commercial test is ready.

The Mysteries of the Ridge, Revealed!

In late June, more than 200 Rhodesian Ridgeback fanciers from across the planet convened in Lund, Sweden, for the 2016 Rhodesian Ridgeback World Congress.

Held every four years, the World Congress is a unique event where the Ridgeback faithful can share views and news, discuss challenges facing the breed, and ignite and rekindle friendships. And last month’s gathering truly raised the bar: Many attendees commented that the line-up of speakers was the among the best of any congress they had attended.

I’d have to agree. Here is just one discussion – I’ll share more in future newsletters – that really set off the lightbulb above my head.

Geneticist Mirko Hornak of the Czech Republic has developed a commercial DNA test that can identify whether a Ridgeback is homozygous or heterozygous for the ridge gene. Other geneticists are offering this service, too, including Jennifer Turner Waldo of the State University of New York at New Palz, who has a DNA test for U.S.-based dogs.

(Quick genetics review: Homozygous dogs, which have two copies of the dominant ridge gene, written in genetic shorthand as RR, can never produce a ridgeless puppy. Heterozygous dogs, which have just one copy of the gene, or Rr, can produce ridgeless if bred to another heterozygote, or a ridgeless. Got it?)

Recently, I’d heard some breeders say that these genetic tests are faulty. Why? Because dogs that were determined to be homozygotes – Ridgebacks that in theory could never produce ridgeless — in fact have produced non-ridged offspring.

Instead, as Mirko and other presenters at the World Congress explained, the ridge mutation, while dominant, has incomplete penetrance. In other words, some dogs may appear to be ridgeless, but are in fact genetically ridged.

In testing Ridgebacks in his lab, Mirko wrote in his abstract for the World Congress, “it was found that sometimes even a dog with one ridge gene (Rr) is ridgeless. This might happen because the ridge gene is very likely silenced,” he posited, adding that no Ridgebacks with two ridge genes (RR) were found to be ridgeless. Mirko estimates that this “silenced” ridge gene occurs in almost 4 percent of puppies produced from homozyogous to heterozygous,or RR x Rr, matings.

This probably explains why persistent oral history in the breed says that ridgeless-to-ridgeless breedings produced ridged offspring. (Even Major Hawley in his landmark book of the breed talks about a Ridgeback being produced from a breeding between ridgeless dogs.) If one of those “ridgeless” dogs was genetically ridged, even though he or she did not have a ridge as we understand the term, then that is indeed possible.

What does this mean for serious students of the breed? We need to understand that it’s not the DNA testing for the ridge gene that’s faulty – it’s our perception of “ridged” that is. While most Ridgeback fanciers understand “ridged” to mean having a very visible stripe of backward-growing hair along the back, genetically “ridged” may mean that just a few hairs are growing against the normal grain of the coat. That follicular disturbance may not be visible to the naked eye, but instead may exist on a molecular level.

(As it happens, I produced one of these “silently ridged” puppies. Click here to see the usual “phantom ridge” that the puppy possessed!)

Curiouser and curiouser! Look for more World Congress views and analysis in upcoming posts …