What breeds lurk in the Ridgeback’s genes? Now, scientists can tell us.

If you’re a Ridgeback history junkie, prepare to become very, very excited.

Some breeds have the luxury of being founded by compulsive individuals with a knack for documentation. The early Boer architects of the Rhodesian Ridgeback, however, were more interested in shooting their supper and avoiding the rake of a leopard’s claws than noodling with pedigrees or preserving parentage. As a result, we have had a very tentative understanding of what breeds went into making the Rhodesian Ridgeback.

Until now.

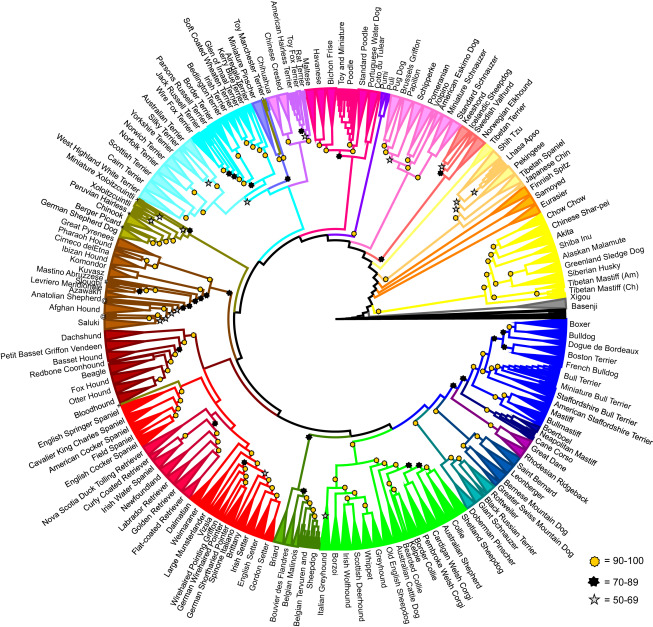

Earlier this week, Cell Reports magazine published a paper called “Genomic Analyses Reveal the Influence of Geographic Origin, Migration, and Hybridization on Modern Dog Breed Development.” To create what is the most diverse data set of dog breeds to date, the researchers studied 161 modern breeds, comparing 170,000 different points on their genomes. They identified 23 clades, or breed clusters, containing breeds that are significantly related.

A graphic showing the 23 clades identified by the researchers. Proximity to another clade is not relevant; what matters are the dogs that share the same color, which reflects their shared genetic heritage. Look for the Ridgeback in the hot-pink clade at about positioned at about the four-o’clock mark.

“There are different reasons logically that a breed could be assigned to a clade,” explains one of the paper’s authors, Dr. Dayna Dreger of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. “Its breeds might be derived from a common source, or it could reflect that there was introgression of one breed into another.”

The scientists assigned the Rhodesian Ridgeback to a clade that has just one other breed:

The Great Dane.

Recruit of Foxbar, a female Great Dane from the 1930s.

If you know your breed history, that canine connection doesn’t come totally out of left field: In her seminal book Rhodesian Ridgeback Pioneers, author Linda Costa shares correspondence from De Beers Ranch officials in Rhodesia in the early 1920s that outlines the diamond mine’s plans to breed Lion Dog sires to recently procured Great Dane bitches. The planned progeny were to be used to hunt vermin on the grounds of the diamond mines, including wild dogs. “I really want rough, big dogs,” one official wrote. ” … the pure Lion Dog appear [sic] too small for the use I need them for in Rhodesia.”

Photographs of Great Danes from the early-20th Century-show dogs that were more moderate in size and type than today’s much more stylized Danes — not too far removed from a modern Ridgeback. And some might argue that Great Dane type is one of the strongest drags on the breed today, manifesting in over-standard size, relative narrowness for that ample height, a squarer silhouette, excessive haw and flews, black masks that extend over the eyes and an overall “extreme” outline.

In addition to grouping breeds into these related clades, the researchers delved into breed make-up. “The paper looked across the admixture of how are breeds created — what was mixed with what to create what,” says Dr. Elaine Ostrander, another of the paper’s authors, who is world famous for her work in purebred-dog genetics.

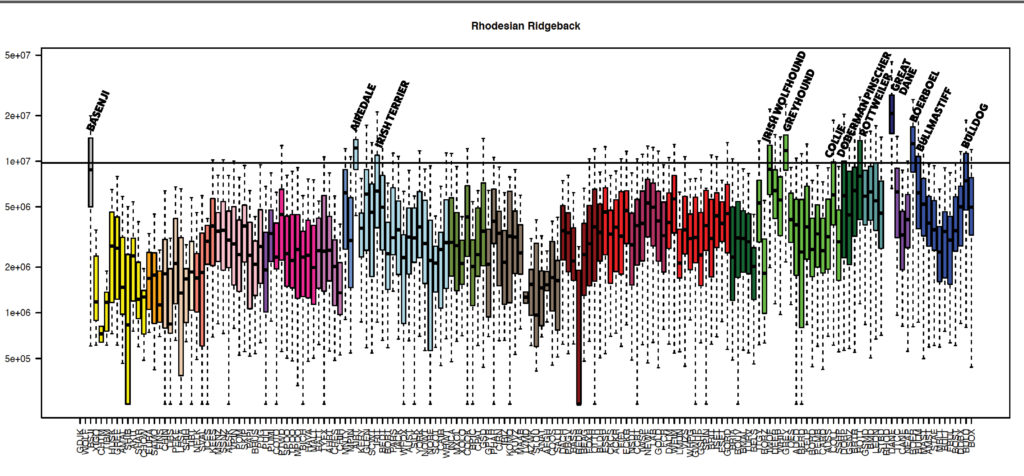

At left are the paper’s findings of the significant genetic influences in the Rhodesian Ridgeback.

At left are the paper’s findings of the significant genetic influences in the Rhodesian Ridgeback.

Let’s take a look at some of the historical and geographic evidence we have of these breeds intersecting with the Ridgeback.

I’ve always found it interesting that there is very little cultural exchange between Rhodesian Ridgeback and Boerbel fanciers. In fact, many of the former are unaware that the Molosser-derived Boerboel developed in tandem with the Ridgeback in the same region of Africa. This lack of awareness could stem from the fact that the breeds had different emphases: Both are hunters and guardians, but the Ridgeback specializes in the former and the Boerboel in the latter. Perhaps the Ridgeback’s development to the north, in Rhodesia, further cementing the division between the two breeds, in the dog fancy at least.

At first glance, having the Basenji place so high on the list of Ridgeback-influencing breeds might seem odd, but this wrinkle-browed dog is a native African, so genetically unique that is has its own singular clade in the study. Sheer geography makes it logical that this purely African breed would have found its way into the Ridgeback gene pool, which is otherwise composed of Continental breeds brought to Africa by European colonizers. Dr. Ostrander notes wryly that the impact of one of the Ridgeback’s most important ancestors, the Khoikhoi dog, can’t be assessed because there are no surviving dogs to provide DNA, though a sampling of ridged Africanis dogs might be the next best thing. And those dogs might prove more closely connected to the Basenji themselves.

The rest of the breeds on the researchers’ list of Ridgeback “introgressors” are European. And they dovetail with surprising precision with the list of founding breeds proposed by the late Canadian breeder-judge David Helgesen in his self-published Definitive Rhodesian Ridgeback.

For the 1984 book, Helgesen analyzed period newspapers to determine what breeds were most common in turn-of-the-last-century Rhodesia, when the breed was formally developed by big-game hunter Cornelius van Rooyen. That, paired with anecdotal accounts of van Rooyen’s pack, led to his oft-repeated list of eight foundation breeds: Greyhound (for speed), Bulldog (for substance and biting power), Irish Terrier and Airedale (for tenacity, and, in the case of the Irish, coat color), Collie (for slashing ability), Pointer (for air scenting ability), Deerhound (for size as well as all the Greyhound’s advantages) and of course the Khoikhoi dog, which contributed the ridge, as well as unknown levels of native knowledge, disease resistance and local adaptability. Other than the Khoikhoi dog and the Irish Wolfhound (which is mostly made up of Deerhound blood, with still more Dane thrown in), only the Pointer is missing from the paper’s list of influential breeds in the Ridgeback — the only real stumper I find in these results.

Genome haplotype sharing for the Rhodesian Ridgeback, from “Genomic Analyses Reveal the Influence of Geographic Origin, Migration, and Hybridization on Modern Dog Breed Development.” Labels added by RidgebackCentral.com.

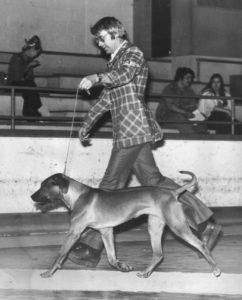

David Helgesen in the ring, 1970s.

Helgesen’s candidates aside, other breeds that come up in the modern DNA findings are logical fits, too. South African diamond mines also used Bullmastiffs for guard and patrol duty, and the Boerboel has a good infusion of Bullmastiff blood itself. Some lines of early Ridgebacks — in particular, Graham Stacey’s Dewsbury and Khami dogs, and those of Phyllis Archdale — had wiry coats accompanied by good size, which strongly evoke the Irish Wolfhound (and so, by extension, the Great Dane), and period articles also mention Wolfhounds being used for lion hunting in Africa. And the occasional black-and-tan has led many Ridgeback fanciers to assume that a two-tone breed — like a Doberman or Rottweiler — jumped the fence somewhere along the line.

In the end, what does all this provide us, other than cocktail-party fodder? For breeders, knowing the Ridgeback’s actual foundation breeds — as well as those that parachuted in later as it developed — helps us chart where our Ridgebacks are heading. Though those who wrote the first Ridgeback standard in 1922 were aiming for a souped-up version of the Dalmatian — that spotted breed’s standard was used to draft the Ridgeback’s, in some places word for word — none of the high-influence breeds in this new genomic study share that basic endurance-trotting silhouette. (Which makes the Pointer’s absence felt even more strongly.)

Ridgeback breeders need to be aware of the genetic influences of other breeds, such as the Great Dane, that can slowly chip away at their breeding programs.

Is it any wonder, then, that Ridgeback type can seem so infuriatingly elusive for those who try to pin it down, either in their whelping boxes, or in the show ring? By knowing what influences lie in the genes of our dogs, we can be more aware when they begin to push breed type in the wrong direction, like a sudden current angling a swimmer away from shore. After all, past is always prologue, and knowing where we’ve been helps us immeasurably in determining where to go next.

Calling all Ridgebacks: Drs. Ostrander and Dreger are looking for Ridgebacks from a variety of lines and countries to continue their genetic work. If you are willing to contribute a blood sample for this research, please contact me at denise@ridgebackcentral.com, and I will put you in touch.

Who needs a ridge, anyway?

Not surprisingly, Ridgeback breed culture has always revolved around the ridge.

Ever since the breed’s name was changed from African Lion Dog to Rhodesian Ridgeback, the message was clear: This native breed of southern Africa was special not because it hunted the king of beasts, but rather for the backward-growing stripe of hair up its back.

Early Ridgeback fanciers in America heard the message loud and clear from their African mentors across the pond: Puppies without ridges were not considered typical of the breed, and were often culled, or euthanized, at birth. (It’s important to remember that 50 years ago, attitudes about companion animals – and their expendability – were significantly different from today.) Thankfully, most modern breeders across the globe see ridgeless puppies for what they are – wonderful, loving pets for the families who are lucky enough to own them.

In this age of tremendous genetic advancement and study, we no longer need a ridge to tell us if a dog is a purebred Ridgeback: His DNA can now tell us.

So that begs the question: Do we need a ridge at all?

I think the answer is yes, for two reasons.

First, the ridge helps the Rhodesian Ridgeback distinguish itself from other athletic, short-coated, red dogs. Some Redbone Coonhounds, for instance, do a very credible Ridgeback impersonation.

Two Redbone Coonhounds. Couldn’t they be confused for Ridgebacks at first glance?

Ridgeback or not? Given the time period — late 19th-Century Germany — likely not.

And take a look at the 19th Century cabinet card at left, which was being sold on eBay as a portrait of a Ridgeback. First of all, there is no historical evidence of Ridgebacks existing in Germany in the 1880s and ’90s, when this photograph was taken; the breed was still in its infancy in southern Africa, and looked very little like the modern breed we know today, which really started to emerge in the 1930s and ’40s.

But if I saw this long-ago dog on the street, I might wonder if he was a brown-nosed Ridgeback – albeit a too-houndy one who had some Labrador Retriever overtones. And I’d check his back for a ridge.

The other reason why we shouldn’t consider the ridge obsolete came up at the Rhodesian Ridgeback World Congress in Sweden over the summer. Geneticist Nicolette Salmon-Hillbertz pointed out that ridges have persisted in the indigenous dogs of southern Africa for millennia, without any interference from humans, and nature doesn’t keep traits around unless they provide some benefit to the animal carrying them. So, she posited, the ridge must be beneficial to Africa dogs – otherwise nature would have long ago extinguished it.

Reinforcing that theory was Helle Lauridsen of Lewanika Ridgebacks in Denmark, who shared this story: When she was living in Western Zambia, working with local craftspeople, she came across a group of refugees from the Angolean war living in the deep roadless bush who had a litter of puppies, all ridged in a wide variety of shapes and places. These ridged puppies were accorded special status: They were well fed and were even permitted to play and sleep inside the dwelling with family members. When Helle asked about buying one of the ridged dogs, she was told most emphatically no: These were very special dogs, the owner explained. Money could buy food for some months, but a good dog could feed a family for years.

Helle takes pains to point out that these villagers had never met a white person before she visited, so they knew of no “myths” surrounding the value of ridged dogs that had come from outside their culture. Rather, their attitude about the value of the ridged dogs was a result of their experience with them for as far back as their oral history extended.

Sometimes there’s more to truth than what can be measured with calipers and yardsticks, so I’m for keeping the ridge, and its mysterious, hidden benefits.

What do you think?

Horsing Around with Ridgebacks

Many years ago, at a dog show in Virginia, I treated myself to a gold pendant of a gaiting Ridgeback. I am fussy about the depictions of the breed that I buy — none of those wrinkled, Mastiff wanna-bes with ridges for me. And this gold-cast Ridgeback was as good as they get, in my opinion.

Recently, I took the piece in to a jeweler and asked him to make up a new bail.”Nice horse,” he said appreciatively.

I corrected him, and noted that he wasn’t the first to make that mistake. And it’s understandable: A good Ridgeback should remind of you of a thoroughbred horse — hard muscled but stylish, effortless but powerful in motion.

That analogy was driven home at the 2016 Rhodesian Ridgeback World Congress this June in Lund, Sweden, where British breeder-judge Ann Woodrow did an in-depth presentation comparing the Ridgeback to its equine counterparts. The dog world has its equivalent of quarter horses, she explained. (Think of a stocky galloper like the Bullmastiff.) On the other end of the spectrum are the Arabians, built for sheer speed and beauty, refinement personified. And somewhere in the middle, Ann reminded, is the thoroughbred — and, for that matter, the Ridgeback.

It’s no coincidence, of course, that the modern Ridgeback standard “borrowed” liberally from the Dalmatian standard of the 1940s. Both breeds are endurance trotters, expected to follow a rider on horseback for hours without breaking down or tiring.

For quite a while now, I’ve been seeing a print of a horse and a Ridgeback popping up on eBay. Painted by Orren Mixer, it features a famous horse, and his not-so-famous Ridgeback companion. The horse, Cutter Bill, born in 1952, was a quarter-horse stallion; as his name suggests, he was a star at the equestrian sport of cutting, a western-style competition in which horse and rider work as a team to demonstrate their athleticism and ability to work cattle. Lep the Ridgeback was Cutter Bill’s stablemate, and their barn in Denton, Texas, is visible in the background of the painting.

Photo courtesy Horse Country USA Archive

Now, to be honest, Lep is not my style Ridgeback: Like many dogs of his era, he was heavier and more roughly made than the dogs we favor today. In this, he follows Ann’s Ridgeback-to-horse comparison quite neatly, looking more like his quarter-horse companion than the more elegant thoroughbreds on which the ideal template of the breed is based.

Both Cutter Bill and Lep were owned by Rex Cauble, a larger-than-life Texan who was convicted in 1982 on racketeering charges for his involvement with the so-called “Cowboy Mafia” marijuana smugglers. Cauble, who died in 2003, maintaining his innocence all the while, could have a hair-trigger temper: An article in Dallas-based D magazine says that when a ranch employee stumbled over Lep, Rex pistol-whipped him for his carelessness.

The millionaire rancher had another at least one other Ridgeback, but Lep appears to have been his favorite.

Catahoula Leopard Dog.

Cauble then bred one of them to a “Leopard Cowdog” — presumably, a Catahoula Leopard Dog, which is a hog-hunting cur named after the Louisiana parish where it was developed. As the photo to the left suggests, but for the merle coat, that breed does evoke the Ridgeback more than most others. Which is probably why Lep, who was named for his Catahoula parent and weighed in at 155 pounds, looked like a purebred Ridgeback — except, perhaps, for his size.

“When he lies on the back seat of Cauble’s Cadillac, he covers it, brother, he covers it!” the story gushed.

And that’s quite enough horsing around for today.

Anatomy of a Ridgeback Brain

The Ridgeback’s 12 Days of Christmas

In December 1997, the last time she permitted herself the luxury of Yuletide décor, Ridgeback lover and rescuer Elise Lewis of Chattanooga, Tennessee, penned a parody of breed-specific holiday mayhem. After posting “The Ridgeback’s 12 Days of Christmas” on a popular email list, and singing it at her office Christmas party, she promptly forgot about it.

But, like the literary version of a designer dog, it soon surfaced in unlikely mutations. “I’ve seen it changed to Shepherd, Xolo, Great Dane, Golden Doodle – any two-syllable dog breed will do,” Elise says.

A less amusing change was Elise’s name morphing into “Author Unknown.”

Here are the lyrics:

On the eleventh day of Christmas, my Ridgeback gave to me:

Eleven unwrapped presents

Ten Christmas cards I shoulda mailed

My wreath in nine pieces

Eight tiny reindeer fragments

Seven scraps of wrapping paper

Six yards of soggy ribbon

Five chewed-up stockings

Four broken window candles

Three punctured ornaments

Two leaking bubbles lights

And the Santa topper from the Christmas tree.

On the twelfth day of Christmas, my Ridgeback gave to me:

A dozen puppy kisses

And I forgot all about the other eleven days.

Excerpted from 100 Memorable Rhodesian Ridgeback Moments