What breeds lurk in the Ridgeback’s genes? Now, scientists can tell us.

If you’re a Ridgeback history junkie, prepare to become very, very excited.

Some breeds have the luxury of being founded by compulsive individuals with a knack for documentation. The early Boer architects of the Rhodesian Ridgeback, however, were more interested in shooting their supper and avoiding the rake of a leopard’s claws than noodling with pedigrees or preserving parentage. As a result, we have had a very tentative understanding of what breeds went into making the Rhodesian Ridgeback.

Until now.

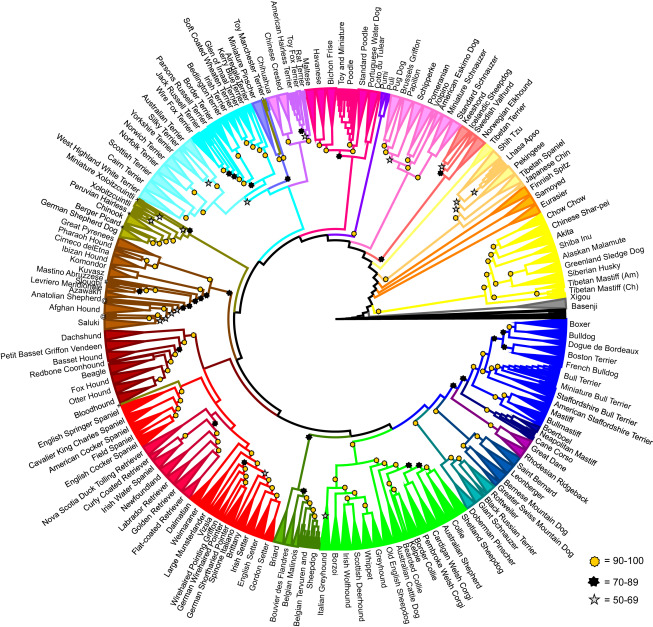

Earlier this week, Cell Reports magazine published a paper called “Genomic Analyses Reveal the Influence of Geographic Origin, Migration, and Hybridization on Modern Dog Breed Development.” To create what is the most diverse data set of dog breeds to date, the researchers studied 161 modern breeds, comparing 170,000 different points on their genomes. They identified 23 clades, or breed clusters, containing breeds that are significantly related.

A graphic showing the 23 clades identified by the researchers. Proximity to another clade is not relevant; what matters are the dogs that share the same color, which reflects their shared genetic heritage. Look for the Ridgeback in the hot-pink clade at about positioned at about the four-o’clock mark.

“There are different reasons logically that a breed could be assigned to a clade,” explains one of the paper’s authors, Dr. Dayna Dreger of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. “Its breeds might be derived from a common source, or it could reflect that there was introgression of one breed into another.”

The scientists assigned the Rhodesian Ridgeback to a clade that has just one other breed:

The Great Dane.

Recruit of Foxbar, a female Great Dane from the 1930s.

If you know your breed history, that canine connection doesn’t come totally out of left field: In her seminal book Rhodesian Ridgeback Pioneers, author Linda Costa shares correspondence from De Beers Ranch officials in Rhodesia in the early 1920s that outlines the diamond mine’s plans to breed Lion Dog sires to recently procured Great Dane bitches. The planned progeny were to be used to hunt vermin on the grounds of the diamond mines, including wild dogs. “I really want rough, big dogs,” one official wrote. ” … the pure Lion Dog appear [sic] too small for the use I need them for in Rhodesia.”

Photographs of Great Danes from the early-20th Century-show dogs that were more moderate in size and type than today’s much more stylized Danes — not too far removed from a modern Ridgeback. And some might argue that Great Dane type is one of the strongest drags on the breed today, manifesting in over-standard size, relative narrowness for that ample height, a squarer silhouette, excessive haw and flews, black masks that extend over the eyes and an overall “extreme” outline.

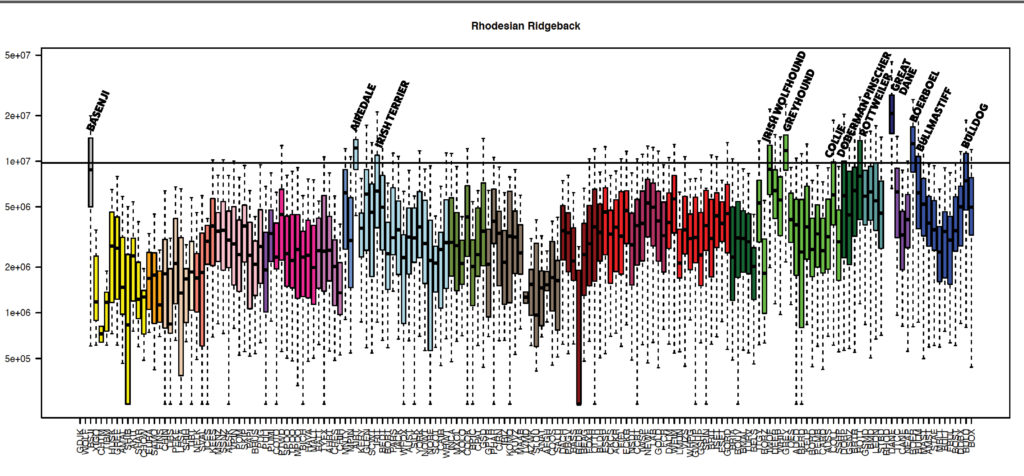

In addition to grouping breeds into these related clades, the researchers delved into breed make-up. “The paper looked across the admixture of how are breeds created — what was mixed with what to create what,” says Dr. Elaine Ostrander, another of the paper’s authors, who is world famous for her work in purebred-dog genetics.

At left are the paper’s findings of the significant genetic influences in the Rhodesian Ridgeback.

At left are the paper’s findings of the significant genetic influences in the Rhodesian Ridgeback.

Let’s take a look at some of the historical and geographic evidence we have of these breeds intersecting with the Ridgeback.

I’ve always found it interesting that there is very little cultural exchange between Rhodesian Ridgeback and Boerbel fanciers. In fact, many of the former are unaware that the Molosser-derived Boerboel developed in tandem with the Ridgeback in the same region of Africa. This lack of awareness could stem from the fact that the breeds had different emphases: Both are hunters and guardians, but the Ridgeback specializes in the former and the Boerboel in the latter. Perhaps the Ridgeback’s development to the north, in Rhodesia, further cementing the division between the two breeds, in the dog fancy at least.

At first glance, having the Basenji place so high on the list of Ridgeback-influencing breeds might seem odd, but this wrinkle-browed dog is a native African, so genetically unique that is has its own singular clade in the study. Sheer geography makes it logical that this purely African breed would have found its way into the Ridgeback gene pool, which is otherwise composed of Continental breeds brought to Africa by European colonizers. Dr. Ostrander notes wryly that the impact of one of the Ridgeback’s most important ancestors, the Khoikhoi dog, can’t be assessed because there are no surviving dogs to provide DNA, though a sampling of ridged Africanis dogs might be the next best thing. And those dogs might prove more closely connected to the Basenji themselves.

The rest of the breeds on the researchers’ list of Ridgeback “introgressors” are European. And they dovetail with surprising precision with the list of founding breeds proposed by the late Canadian breeder-judge David Helgesen in his self-published Definitive Rhodesian Ridgeback.

For the 1984 book, Helgesen analyzed period newspapers to determine what breeds were most common in turn-of-the-last-century Rhodesia, when the breed was formally developed by big-game hunter Cornelius van Rooyen. That, paired with anecdotal accounts of van Rooyen’s pack, led to his oft-repeated list of eight foundation breeds: Greyhound (for speed), Bulldog (for substance and biting power), Irish Terrier and Airedale (for tenacity, and, in the case of the Irish, coat color), Collie (for slashing ability), Pointer (for air scenting ability), Deerhound (for size as well as all the Greyhound’s advantages) and of course the Khoikhoi dog, which contributed the ridge, as well as unknown levels of native knowledge, disease resistance and local adaptability. Other than the Khoikhoi dog and the Irish Wolfhound (which is mostly made up of Deerhound blood, with still more Dane thrown in), only the Pointer is missing from the paper’s list of influential breeds in the Ridgeback — the only real stumper I find in these results.

Genome haplotype sharing for the Rhodesian Ridgeback, from “Genomic Analyses Reveal the Influence of Geographic Origin, Migration, and Hybridization on Modern Dog Breed Development.” Labels added by RidgebackCentral.com.

David Helgesen in the ring, 1970s.

Helgesen’s candidates aside, other breeds that come up in the modern DNA findings are logical fits, too. South African diamond mines also used Bullmastiffs for guard and patrol duty, and the Boerboel has a good infusion of Bullmastiff blood itself. Some lines of early Ridgebacks — in particular, Graham Stacey’s Dewsbury and Khami dogs, and those of Phyllis Archdale — had wiry coats accompanied by good size, which strongly evoke the Irish Wolfhound (and so, by extension, the Great Dane), and period articles also mention Wolfhounds being used for lion hunting in Africa. And the occasional black-and-tan has led many Ridgeback fanciers to assume that a two-tone breed — like a Doberman or Rottweiler — jumped the fence somewhere along the line.

In the end, what does all this provide us, other than cocktail-party fodder? For breeders, knowing the Ridgeback’s actual foundation breeds — as well as those that parachuted in later as it developed — helps us chart where our Ridgebacks are heading. Though those who wrote the first Ridgeback standard in 1922 were aiming for a souped-up version of the Dalmatian — that spotted breed’s standard was used to draft the Ridgeback’s, in some places word for word — none of the high-influence breeds in this new genomic study share that basic endurance-trotting silhouette. (Which makes the Pointer’s absence felt even more strongly.)

Ridgeback breeders need to be aware of the genetic influences of other breeds, such as the Great Dane, that can slowly chip away at their breeding programs.

Is it any wonder, then, that Ridgeback type can seem so infuriatingly elusive for those who try to pin it down, either in their whelping boxes, or in the show ring? By knowing what influences lie in the genes of our dogs, we can be more aware when they begin to push breed type in the wrong direction, like a sudden current angling a swimmer away from shore. After all, past is always prologue, and knowing where we’ve been helps us immeasurably in determining where to go next.

Calling all Ridgebacks: Drs. Ostrander and Dreger are looking for Ridgebacks from a variety of lines and countries to continue their genetic work. If you are willing to contribute a blood sample for this research, please contact me at denise@ridgebackcentral.com, and I will put you in touch.